The battle for Europe is also being fought online. Russia wants to weaken EU cohesion, NATO coordination and support for Ukraine; the Netherlands’ parliamentary elections are an obvious target. On social media, this manifests itself in polarising narratives and coordinated amplification: identical slogans, “response sprints” and suspicious followers who tip the balance of visibility. Last week, we saw concrete signs of this on Dutch party social media channels. We have no direct evidence to point to Russia, but the mechanism is very similar to recent pro-Kremlin campaigns in Moldova.

The Netherlands as a target

Although Moldova and the Netherlands differ greatly in political terms, Russia can use the same tactics to exert similar influence and manipulation. Due to the transnational and borderless nature of social media, bots and paid users can easily be deployed to spread large-scale disinformation campaigns aimed at polarisation and division within the country. Given the existing political will and social acceptance of protests in the Netherlands, Russia may not need to invest much financial resources here. Stirring up provocative discussions and spreading disinformation is already sufficient to have a noticeable effect. Moreover, many of the possible Russian narratives contain themes that are already being promoted by various extremist groups in the Netherlands. Examples that directly align with the narratives promoted by Russia include: ‘The EU only costs money,’ ‘The EU is anti-Netherlands,’ ‘Integration of Moldova would only bring criminals to Europe,’ and anti-LGBTI sentiments.

Some eligible parties in the Netherlands express ambitions that work to Russia’s advantage. Techniques often used in EU Member States mainly revolve around disinformation and sabotage. Vote buying is less conspicuous in the Netherlands – it would require a considerably larger investment – but the amplification of certain political voices through artificial interaction, the dissemination of fake news and the vilification of European-oriented governments and political parties is widespread. Russia is currently using AI in several regions to automatically generate texts that are related to a specific context and therefore do not match identically. We have often observed this in messages on Telegram about the Moldovan elections.* Nevertheless, a striking factor remains the high activity of social media users who have empty, newly created accounts. Often with language that is out of place and repetitive.

Striking behaviour

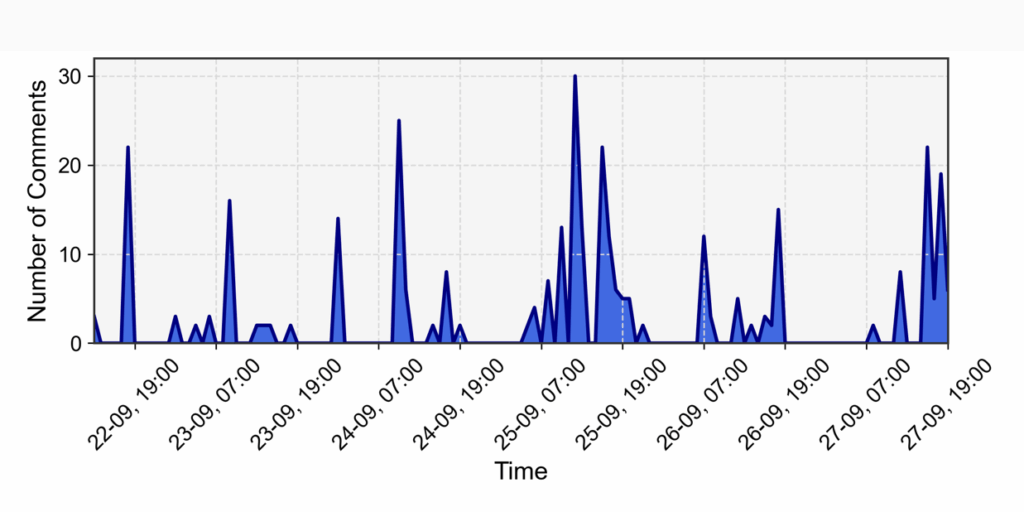

To illustrate this type of behaviour, we conducted a small sample survey of recent comments under posts on Facebook and Instagram and videos on YouTube. A clear sign of inauthentic behaviour is spamming. One user posted the comments ‘Without NEXIT, nothing will change’ (28 times in one week) and ‘Vote FVD. NEXIT NOW’ (35 times in one week) under various political party accounts. Another user commented ‘I’m voting FVD’ (20 times in one week) under posts from political Facebook accounts. Some accounts also post rapid series of multiple comments in a short period of time, known as ‘comment sprints’.

A sign of inauthentic behaviour: frequent responses in a short period of time, measured here on the channels of political parties and candidates in the House of Representatives elections. For example, we see here that on 25 September 2025, at around 7 a.m., one account posted no fewer than 30 responses in a very short period of time.

On the other hand, artificially inflating the number of likes and shares of posts can also have an effect on which messages receive the most exposure, and some accounts have a large number of fake followers.

Treacherous

One of the characteristics of state interference in Western European countries, such as the Netherlands, is that it is generally much less visible than in countries such as Moldova. Russia first focuses on neighbouring countries where it can immediately feel the impact. According to Ukrainian intelligence services, around $350 million (equivalent to 2% of Moldova’s GDP) was spent around the Moldovan elections, enough for large-scale offline campaigns. While in the Netherlands it is not that visible, here it is precisely its invisible nature that makes the influence of foreign interference so treacherous.

*An example of messages we observed were Russian responses to a Telegram message about weather changes in Moldova. Five different accounts with Romanian names responded in Russian with an identical message: “All problems in Moldova are due to President Sandu, including this new problem of bad weather”. Each comment was written in correct language, but each time with slightly different wording.

Defend Democracy, 10 October 2025